Long before completing my biomedical PhD, I knew I wanted a career where I could see the scientific progress in the lab be reflected in the real world, particularly with regards to improved human health. Now, funded through the TL1 Translational Sciences Postdoctoral Program under the Entrepreneurship track, I have the opportunity to do just that through the Skandalaris Center. As one of the newest members of the team, I will spend my fellowship working with the LEAP gap-fund to become versed in the language of biomedical entrepreneurship and support WashU inventors as they move their project from the lab to the market.

As part of my TL1 fellowship training, I also attend career development seminars, most of which are also open to the WashU community. A recent talk by science communication expert Melissa Marshall was particularly impactful for me, and I believe the takeaways are worth sharing. The seminar, entitled “Present your Science," addressed common problems with how most scientific PowerPoints are given and provided research-based best practices to help improve them.

Chief among the impediments to the presenting process was, to many in the audience’s amusement, the default PowerPoint slide template. This may or may not be surprising to you, as the default bullet point style is almost ubiquitous in scientific talks. However, if you’ve ever attended a dense technical talk that relied heavily on bullet points, you may have already realized the problem. In these situations, audience members tend to primarily focus on the text, on the speaker’s words, or sporadically switch back and forth. This can lead to poor comprehension, as the audience is always missing out on part of the presented information.

This phenomenon is well-studied in the field of cognitive psychology. To be brief, the spoken and textual information presented in these scenarios are both verbally encoded, and thus utilize the same “cognitive pathway” in our brains. Like the backup that occurs when two lanes of traffic are suddenly forced to merge into a single lane, presentations that contain too much textual information can easily lead to an overload of the verbal pathway.

In an attempt to make the slides more engaging, many presenters add images, graphs, or other visual aids related to the topic of the slide. However, while it is true that visual information uses a separate, nonverbal “cognitive pathway," frequently, the images used are distracting or irrelevant. The use of visual aids in this manner only serves to distract from the point of the slide and can further decrease audience comprehension.

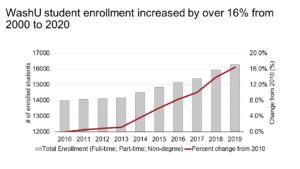

So, what’s the solution? Enter the “Assertion-Evidence” approach, which applies the findings from cognitive psychology to build presentations that are compatible with how we learn (https://www.assertion-evidence.com/). The first two principles of this model dictate that presentation slides should be built around full-sentence messages, rather than topics, and that these messages should be supported using visual evidence. To provide a simple example, a slide titled “WashU Student Enrollment: 2000-2020” with bullet points listing every 5th year and respective population size could be changed to “WashU student enrollment increased by X% from 2000 to 2020” with a line graph that visually depicts the data over time. Finally, the third principle of this model states that the presenter should explain the evidence spontaneously, rather than reciting a prepared script.

No matter your field of study, if you ever use slides to present, these principles can likely help you create more understandable and confident presentations. I believe the methods discussed above could also be useful for new entrepreneurs, as they must be able to translate the often-complicated aspects of their idea to companies or investors. I encourage all of those interested in learning more to check out the resources below and to attend some of the Skandalaris Center events focused on presentations and communicating your ideas.

Garner, Joanna K., Michael Alley, Allen Gaudelli, and Sarah Zappe (2009). The common use of PowerPoint versus the assertion–evidence structure: A cognitive psychology perspective. Technical Communication, 56 (4).

Assertion-Evidence resources and examples: https://www.assertion-evidence.com/

Melissa’s Website: https://www.presentyourscience.com/

Melissa’s TED Talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/melissa_marshall_talk_nerdy_to_me?language=en